'A Whole Barena' - collaboration with the photographer Matteo de Mayda

'A Whole Barena"

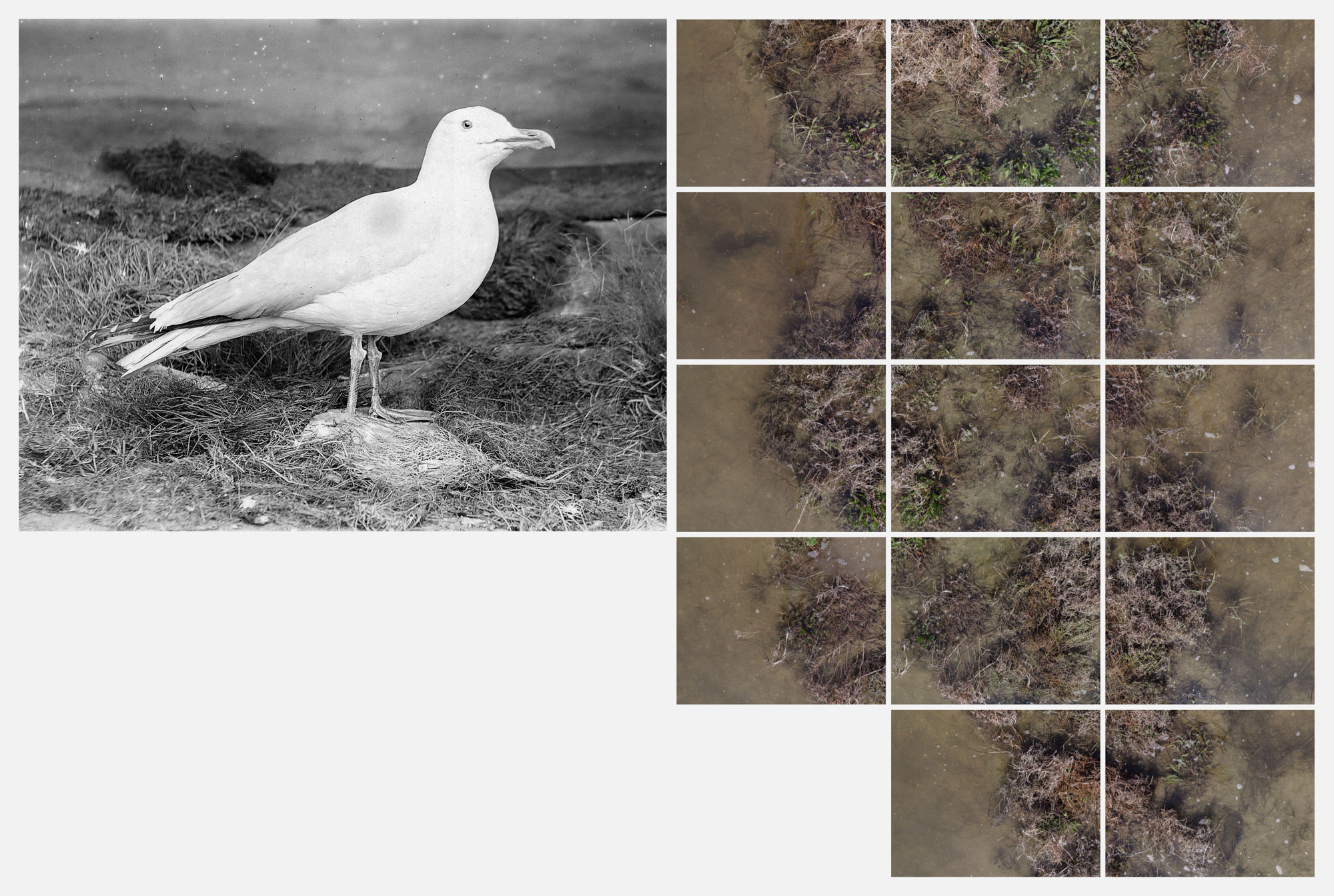

The photographer Matteo de Mayda, in collaboration with We are here Venice within the Vital initiatives, recently presented the project 'A Whole Barena' as part of 'Nuova Generazione. Contemporary looks at the Alinari Archives", by CAMERA and the Alinari Foundation for Photography. The project was exhibited for the first time last October at CAMERA in Turin in the form of photographs taken from above of a barena, combined with a selection of characteristic salt marsh birds from the Alinari Archives.

Here is an excerpt from Eleonora Sovrani's interview with Matteo de Mayda:

ES: Why did you decide to start this photographic project on the Venice lagoon?

MdM: My photography is often based on scientific research and I usually rely on inputs from associations, research institutions that interest me, to interpret findings not in an exhaustive way, but through my own poetics. In this case, I thought of the Lagoon of Venice because I live in Venice and on the one hand I think it’s right to delve into the relevant themes, on the other I was motivated by my curiosity to explore the world I live in and to understand it a little better. Moreover, last year I had met We are here Venice, which inspired various reflections on this theme, and this would give us an opportunity to collaborate.

ES: What kind of dialogue did you have with the experts and scientists with whom you collaborated?

MdM: I decided to focus on the theme of salt marshes, especially after my meeting with We are here Venice and after some reading that you suggested, such as the Villa Frankenstein project, in which I found key basic information on the flora and fauna of salt marshes. Then I started thinking how to connect my photographic practice with images from the Alinari archive, as required by the project, and with my research on the Venice lagoon. Through the material you shared with me, I realised that birdlife is a very strong indicator of the health of the salt marshes and therefore of the lagoon, so I thought it was an interesting road to take. I thought I wanted to bring an entire barena into the exhibition for the CAMERA project, and I also wanted to tell the story of the avifauna through the Alinari archive materials. The search [for a common thread] was not easy: at first I just looked for images using the terms 'Venice' and 'Lagoon', but the results obtained were mainly related to typical postcard images, of monuments, canals and views of St. Mark's Square.

By discussing this with you and with Alessandro Sartori, an ornithologist, and by listening to various anecdotes related to bird migration, an awareness of the indefiniteness of boundaries and that humans and birds interpret them quite differently grew in me. So I began not to limit myself to words strictly related to Venice when exploring archive images, but broadened my perspective to include the names of the birds that inhabit the lagoon, thanks to the information I had acquired in the field of ornithology.

In doing so, I discovered a rich series of birds photographed by Coburn around 1890, with studio reconstructions of their original environment; the fact that these had an English provenance no longer mattered: just as birds have a different definition of boundaries, I allowed myself to have one too. Together with you and Sartori, we then defined which species should be included to tell the story of the lagoon. Another set of images of birds came from the early 19th century collection of the illustrator and ornithologist John James Audubon. From those images we selected the sacred ibis, because we felt it was particularly effective in telling the story of the lagoon and the alien species that inhabit it now.

ES: Were there any aspects that you didn't know or didn't expect before undertaking the fieldwork that made you change your initial concept?

MdM: After the first meeting with you, I discarded the idea of shooting the saltmarsh with a drone, because it would have excluded some fundamental aspects of the barena, such as the marks left by birds, crabs, and the waves that sometimes bring rubbish. So I decided to photograph the marsh piece by piece - in my head I initially thought I would use a tripod, following a grid created on the spot with string; but when I found the site I realised that I would have struggled to stay standing, so it would have been impossible to take precise measurements. The first challenge was figuring out how to photograph the saltmarsh accurately, but then I realised the oxymoron: photographing a saltmarsh in the same state is impossible, because it is constantly changing in relation to the tides; admitting the visual inconsistencies, therefore, also allows us to address this aspect. In the 60 images of the CAMERA exhibition, the shape of the barena is recognisable, but in the juxtaposed details it is very imprecise, and this emphasises its continuous changing.

ES: What would you suggest to people who want to learn more about the barene of the Venice Lagoon?

MdM: In my opinion, visiting the lagoon with someone who is an expert on the saltmarsh and its flora and fauna is invaluable. For example, the ornithologist who accompanied me during the explorations also explained how to move around without disturbing the birds, e.g. without gesturing or pointing. It is also important to remember that waves caused by boat traffic, besides eroding the edges of the saltmarsh, can also wash away birds' eggs, so, even when in a boat, it is important to move slowly and with respect.

◾